Dark Matter

In astronomy and cosmology, Dark Matter is hypothetical matter that does not interact with the electromagnetic force, but whose presence can be inferred from gravitational effects on visible matter. According to present observations of structures larger than galaxies, as well as Big Bang cosmology, dark matter and dark energy account for the vast majority of the mass in the observable universe. The observed phenomena which imply the presence of dark matter include the rotational speeds of galaxies, orbital velocities of galaxies in clusters, gravitational lensing of background objects by galaxy clusters such as the Bullet cluster, and the temperature distribution of hot gas in galaxies and clusters of galaxies. Dark matter also plays a central role in structure formation and galaxy evolution, and has measurable effects on the anisotropy of the cosmic microwave background. All these lines of evidence suggest that galaxies, clusters of galaxies, and the universe as a whole contain far more matter than that which interacts with electromagnetic radiation: the remainder is called the "dark matter component."

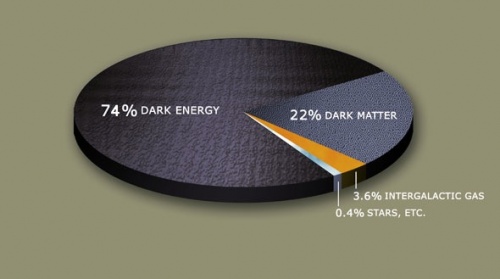

The dark matter component has much more mass than the "visible" component of the universe. At present, the density of ordinary baryons and radiation in the universe is estimated to be equivalent to about one hydrogen atom per cubic meter of space. Only about 4% of the total energy density in the universe (as inferred from gravitational effects) can be seen directly. About 22% is thought to be composed of dark matter. The remaining 74% is thought to consist of dark energy, an even stranger component, distributed diffusely in space. Some hard-to-detect baryonic matter is believed to make a contribution to dark matter but would constitute only a small portion. Determining the nature of this missing mass is one of the most important problems in modern cosmology and particle physics. It has been noted that the names "dark matter" and "dark energy" serve mainly as expressions of human ignorance, much like the marking of early maps with "terra incognita."

Observational Evidence

The first to provide evidence and infer the existence of a phenomenon that has come to be called "dark matter" was Swiss astrophysicist Fritz Zwicky, of the California Institute of Technology in 1933. He applied the virial theorem to the Coma cluster of galaxies and obtained evidence of unseen mass. Zwicky estimated the cluster's total mass based on the motions of galaxies near its edge. When he compared this mass estimate to one based on the number of galaxies and total brightness of the cluster, he found that there was about 400 times more mass than expected. The gravity of the visible galaxies in the cluster would be far too small for such fast orbits, so something extra was required. This is known as the "missing mass problem". Based on these conclusions, Zwicky inferred that there must be some non-visible form of matter which would provide enough of the mass and gravity to hold the cluster together.

Much of the evidence for dark matter comes from the study of the motions of galaxies.Many of these appear to be fairly uniform, so by the virial theorem the total kinetic energy should be half the total gravitational binding energy of the galaxies. Experimentally, however, the total kinetic energy is found to be much greater: in particular, assuming the gravitational mass is due to only the visible matter of the galaxy, stars far from the center of galaxies have much higher velocities than predicted by the virial theorem. Galactic rotation curves, which illustrate the velocity of rotation versus the distance from the galactic center, cannot be explained by only the visible matter. Assuming that the visible material makes up only a small part of the cluster is the most straightforward way of accounting for this. Galaxies show signs of being composed largely of a roughly spherically symmetric, centrally concentrated halo of dark matter with the visible matter concentrated in a disc at the center. Low surface brightness dwarf galaxies are important sources of information for studying dark matter, as they have an uncommonly low ratio of visible matter to dark matter, and have few bright stars at the center which impair observations of the rotation curve of outlying stars.

Gravitational lensing observations of galaxy clusters allow direct estimates of the gravitational mass based on its effect on light from background galaxies. In clusters such as Abell 1689, lensing observations confirm the presence of considerably more mass than is indicated by the clusters' light alone. In the Bullet Cluster, lensing observations show that much of the lensing mass is separated from the X-ray-emitting baryonic mass.

Nonbaryonic Dark Matter

Nonbaryonic dark matter refers to substances containing no atoms and does not interact with electromagnetic forces, such as black holes, axions, and supersymmetric particles. Dark matter is hypothetical in itself, not to mention the nonbaryonic form. As dark matter has no true shape or being, it is easily imaginable without atoms. This form of dark matter has extremely high or low mass, contributing to the dissimilarities in galaxy rotation curves. There are three promininent theories on nonbaryonic dark matter, which are Hot Dark Matter (HDM), Warm Dark Matter (WDM), and Cold Dark Matter (CDM), where WDM is a merger between the other two theories. This sort of dark matter normally deals with hypothetical calculations about what happens in a black hole, around a black hole, and forming a black hole. Although there are still many skeptics, nonbaryonic dark matter is generally accepted as existing, even in our own galaxy.